Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

(If the slides don’t work, you can still use any direct links to recordings.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Lecture 09:

Mind & Reality

\def \ititle {Lecture 09}

\def \isubtitle {Mind & Reality}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

Propositions Individuate Contents

\section{Propositions Individuate Contents}

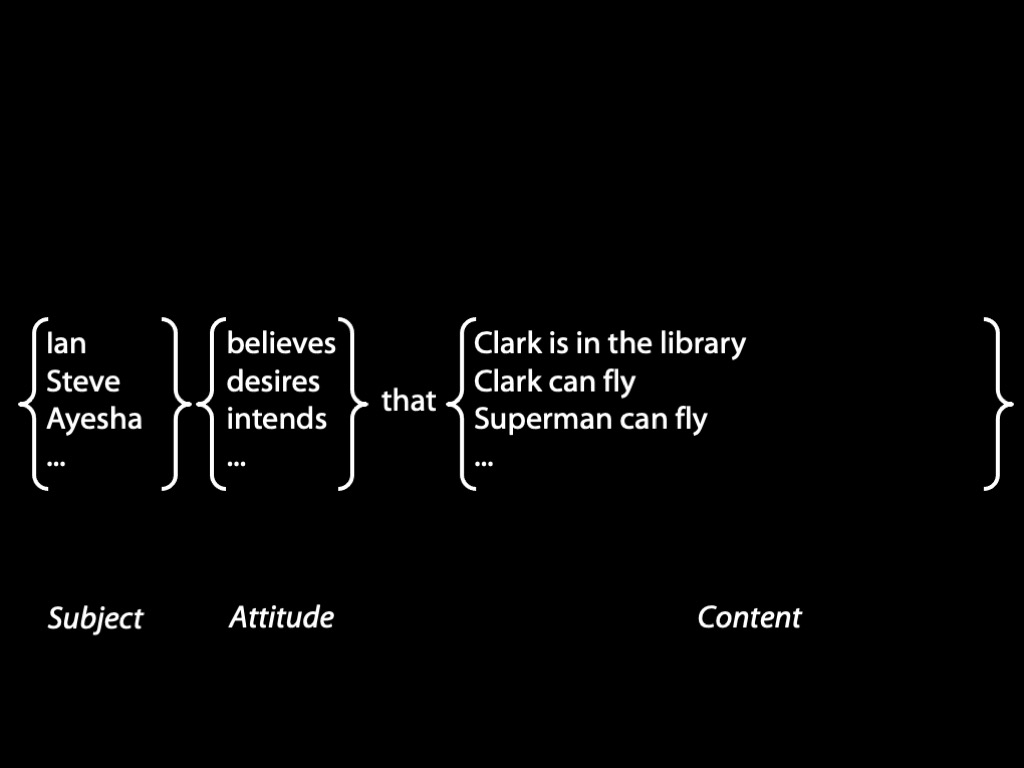

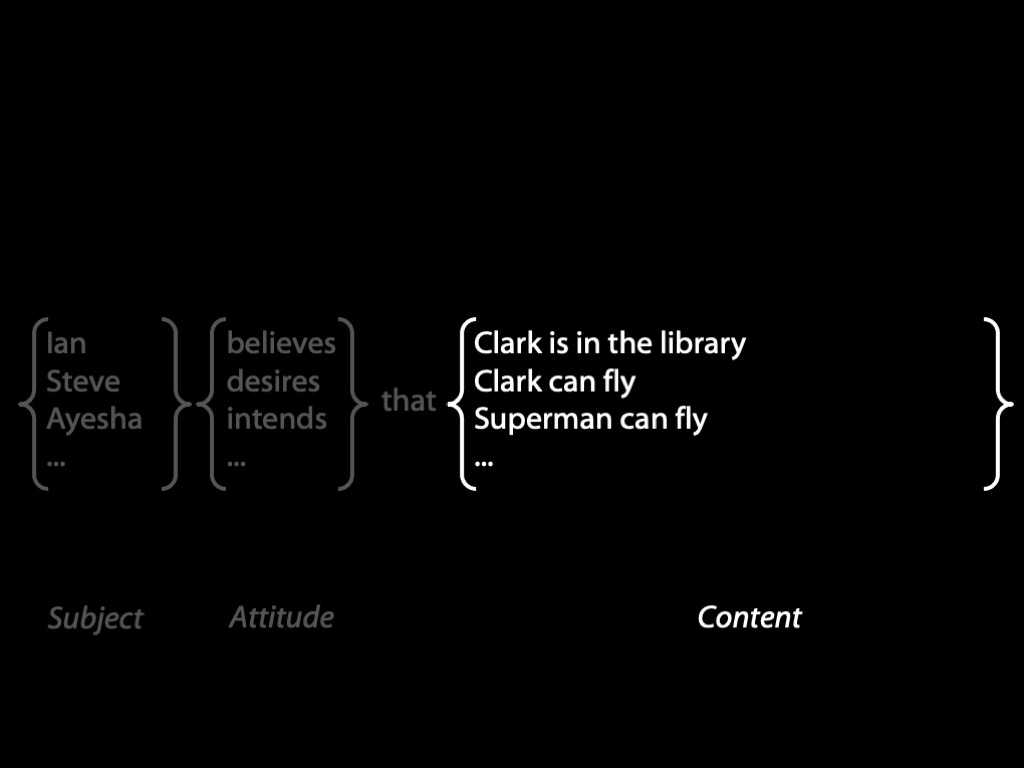

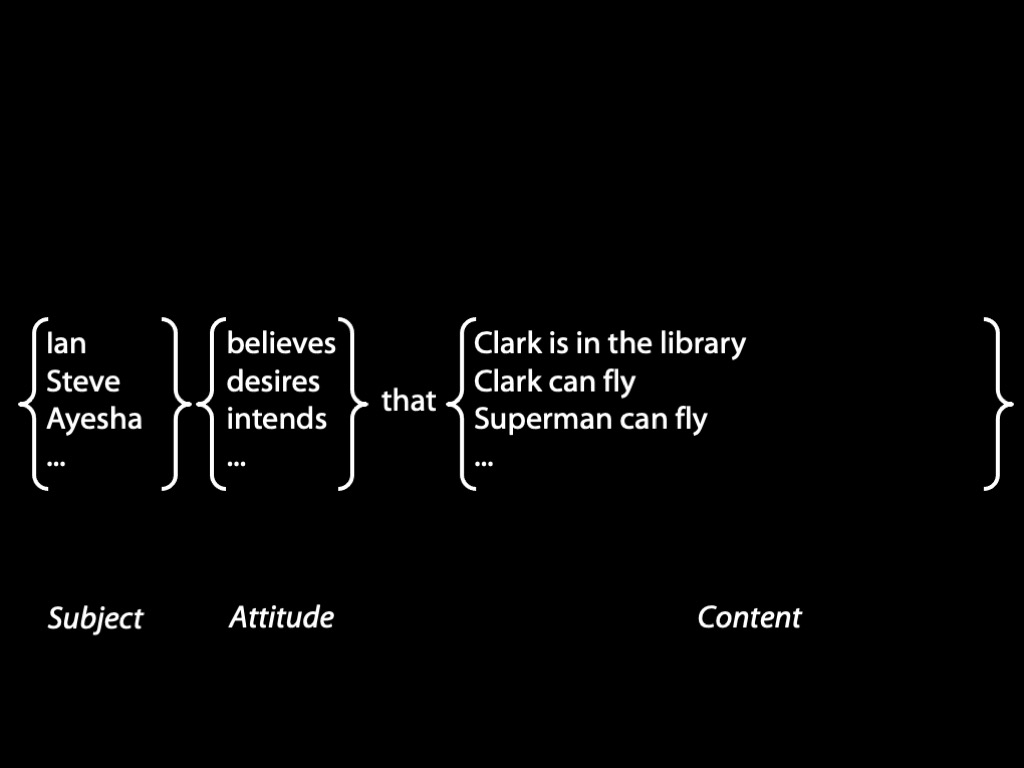

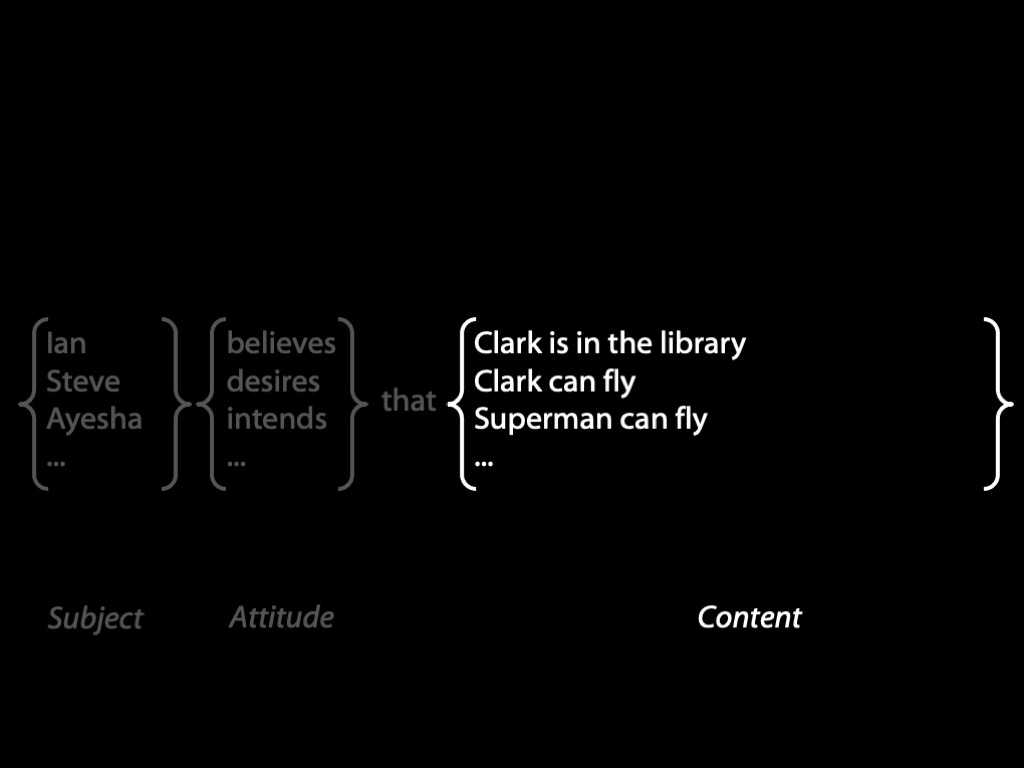

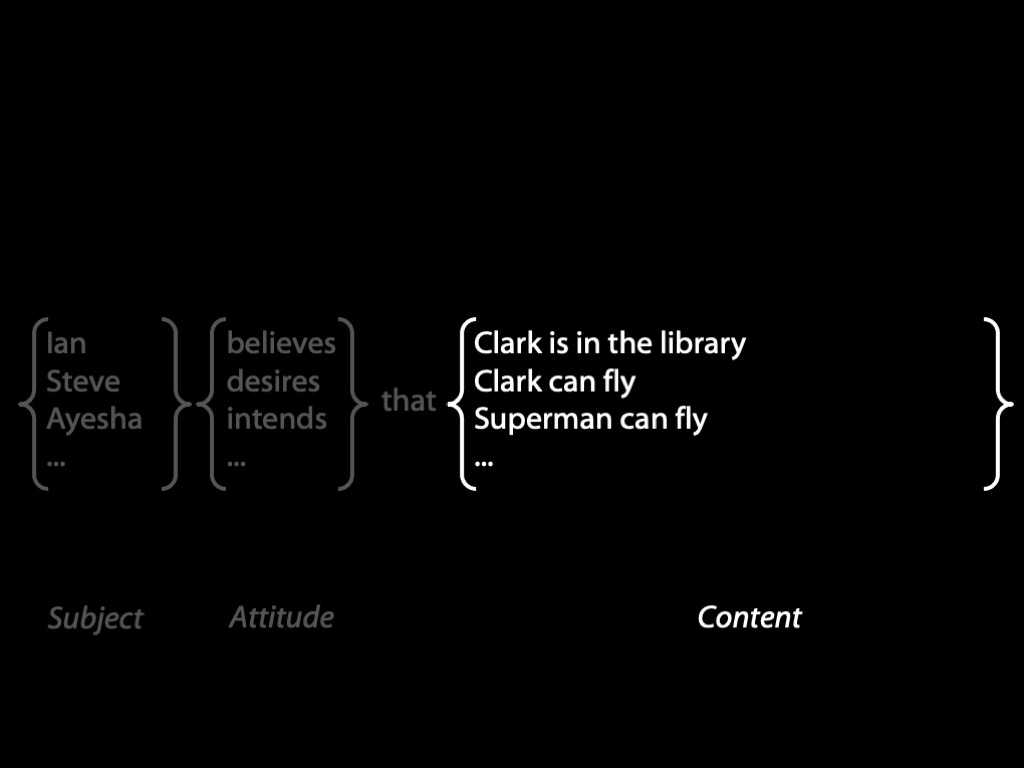

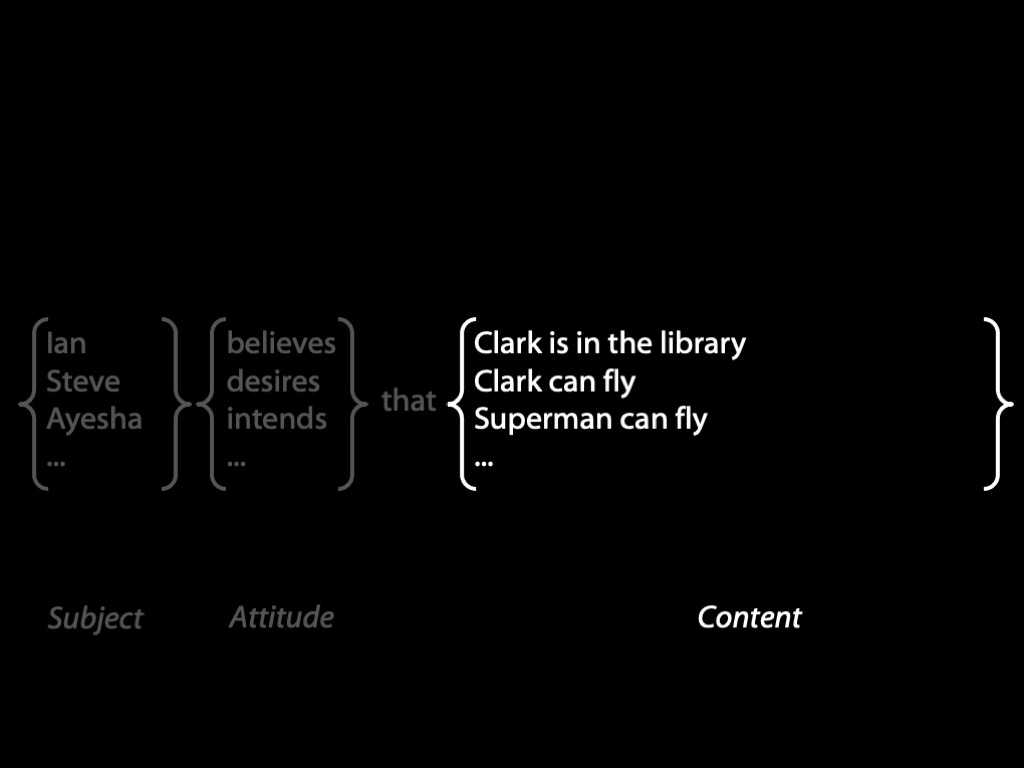

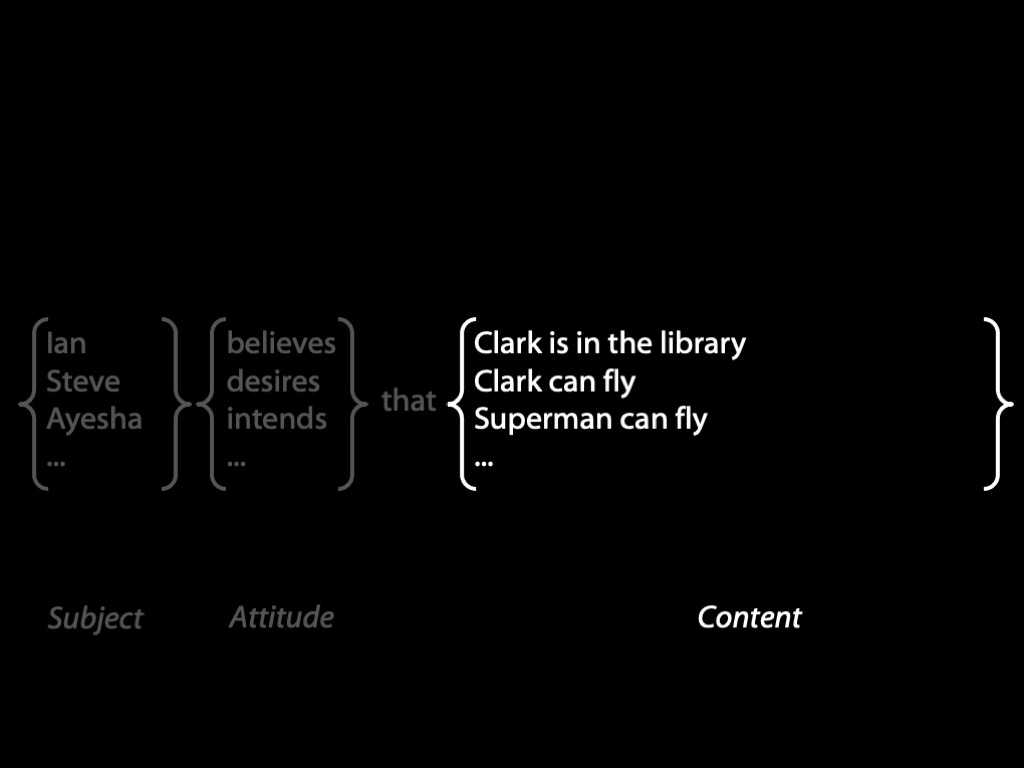

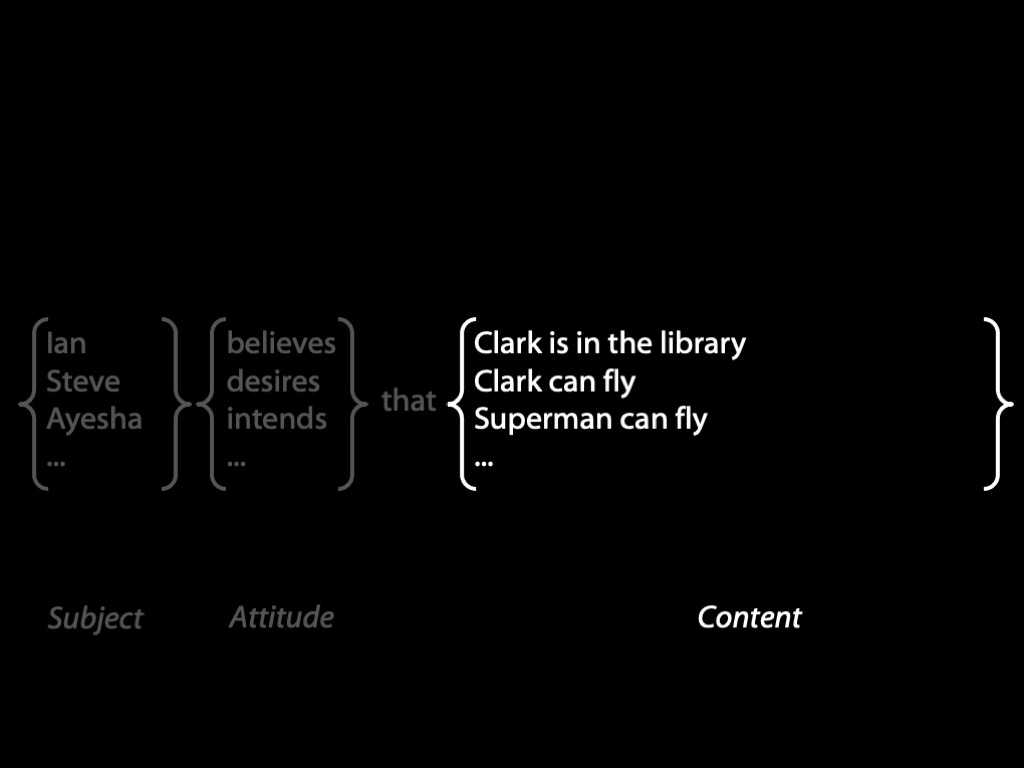

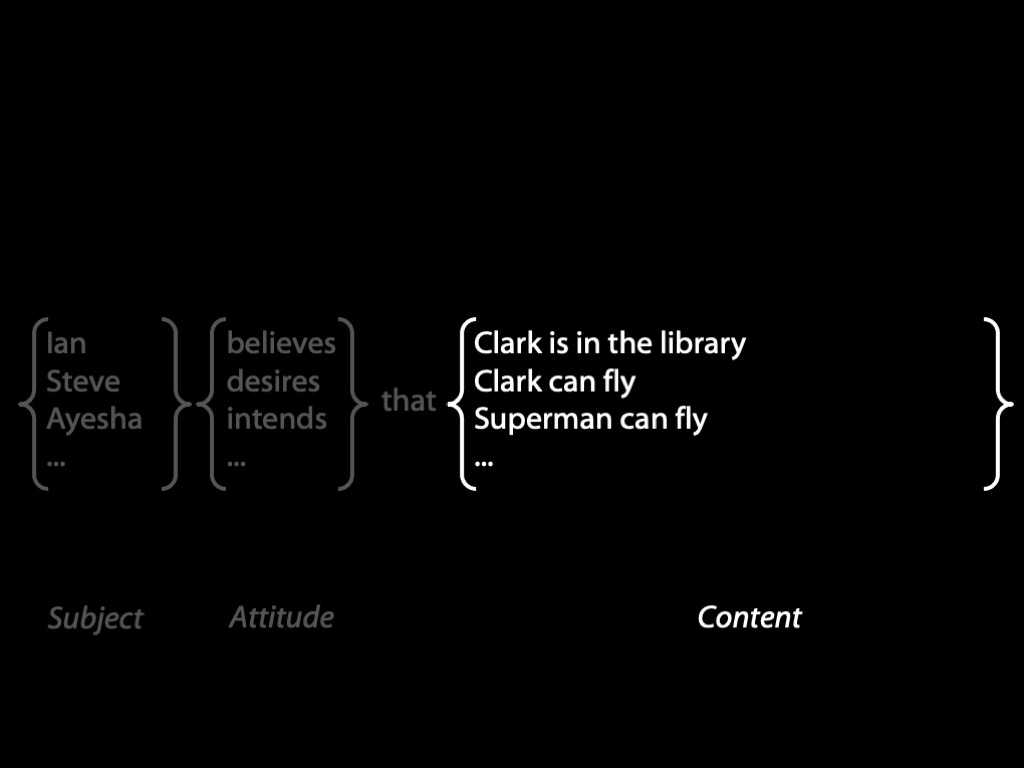

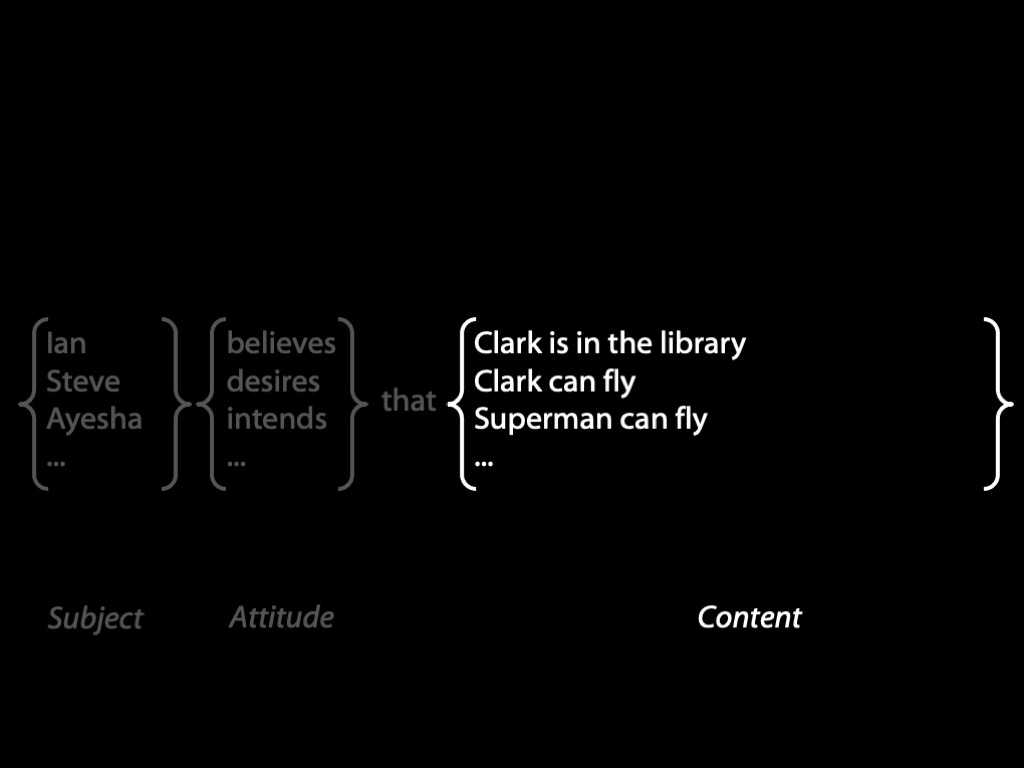

We’ve seen that mental states have three basic components.

Let’s focus on the content.

How do we distinguish the contents of mental states?

You and I distinguish the contents of mental states every day.

In one sense, this is trivial.

It’s something we do all the time.

I might say, Ayesha wants you to drive her, she does not want me to drive her.

Here I’m distinguishing between two desires.

Or you might say, ‘Lois believes superman can fly, but she doesn’t know that Clark can fly’

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

This is a much harder question to answer.

ME: Someone ate my breakfast.

YOU: Steve thinks someone ate his breakfast.

Sentences have features which make them unsuitable for distinguishing the contents of mental states ...

Indexicality

‘It’s raining’

‘Logic makes me die inside’

Ambiguity

‘You have to turn your headlamps on

when it’s raining in Sweden.’

How do I know it’s raining in Sweden?

Pragmatic features

‘Dogs must be carried.’ / ‘Shoes must be worn.’

‘Someone ate my breakfast..’

It was me.

‘I’ve had a great evening.’

This wasn’t it.

Sentences are not true or false.

Sentences do not correspond to ways the world could be.

The contents of mental states can be true or false.

The contents of mental states do correspond to ways the world could be.

Therefore, sentences are unsuitable for distinguishing, the contents of mental states.

How do we distinguish the contents of mental states?

You and I distinguish the contents of mental states every day.

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

This is a much harder question to answer.

- sentences?

- utterances?

No because these have a date. We want to say distinguish contents in this way:

when two attitudes have the same content, we use the same thing to distingish them.

(The relation between a content to thing-that-distinguishes-it-from-all-other-contents should not

be a one-many relation)

Summary So Far

We need propositions to distinguish the contents of mental states.

But what are propositions?

/ex/q/Why does the fact that sentences can be ambiguous make them unsuitable for distinguishing the contents of mental states?

\section{Propositions}

\emph{Reading:} §McGrath, Matthew and Devin Frank, "Propositions", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/propositions/, §King, Jeffrey C. ‘Structured Propositions’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2019. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/propositions-structured/

I was just asking,

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

- sentences?

- utterances?

- propositions

The correct answer is, propositions. But what are propositions?

Propositions can be true or false.

The truth-value of a proposition does not change.

Propositions are abstract objects (like numebrs).

Unlike sentences.

Unlike utterances (which are events, with a date and time).

A

1. What Ayesha said is true.

2. Sentences are not the kinds of thing that can be true or false.

3. Therefore what Ayesha said is not a sentence

B

1. What Ayesha said is what Steve said.

2. Ayesha’s utterance is not Steve’s utterance.

3. Therefore what Ayesha said is not a utterance.

Is what Ayesha said a proposition?

Propositions

... are the things that can be true or false;

... might be the things that utterances characteristcally express.

But what are propositions?

View 1

Propositions are sets of possible worlds.

This proposition is true in all possible worlds:

2^16 is 65536

These propositions are true in the same possible worlds.

[A] Charly is a secret agent

[B] Charly is a secret agent and 2^16 is 65536.

Ayesha could know [A] while not knowing [B].

But if propositions are sets of possible worlds, [A] and [B] are not disinct.

Therefore propositions-as-sets-of-possible worlds do not fully enable us to capture Ayesha’s point of view.

View 2

Propositions are sets of objects, properties and functions.

Let S stand for the property of being a secret agent.

Notation: <...> is an orderd tuple.

The proposition

<S, Charlie>

might be used to individuate the content of Ayesha’s belief that Charlie is a secret agent.

The proposition

<AND, <S, Charlie>, <EQUALS, <POWER, 2, 16>, 65536>>

might be used to individuate the content of someone’s belief that Charlie is a secret agent and 2&16 is 65536.

So what are propositions?

There are different kinds of proposition (like numbers) ...

Lewisian propositions are sets of possible worlds.

Russellian propositions are sets of objects, properties and functions.

I was just asking,

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

- sentences?

- utterances?

- propositions

-- but not Lewisian propositions

-- maybe Russellian propositions?

/ex/TorF/qq/Propositions can be true or false|Propositions are sentences|Logic makes your lecturer die inside

\section{Frege and Propositions}

\emph{Reading:} §Frege, G. (1980). Letter to jourdain. In Kaal, Hans (trans), Philosophical and mathematical correspondence, pages 78–80. (Find the letter online by searching for the terms ‘frege’, ’etna’ and ‘ateb’.), §Section 3.1.1 and the first paragraph of Section 3.2 of Zalta, Edward N., "Gottlob Frege", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

I was just asking,

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

- sentences?

- utterances?

- propositions

-- but not Lewisian propositions

-- maybe Russellian propositions?

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Charly is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Charlie>

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Samantha is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Samantha>

Charly = Samantha

Therefore <S, Charlie> = <S, Samantha>

Russell: what goes into the proposition is the thing itself (Charly).

Frege: what goes into the proposition is not the thing itself (Charly) but a sense.

I was just asking,

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

- sentences?

- utterances?

- propositions

-- but not Lewisian propositions

-- maybe Russellian propositions?

-- maybe Fregean propositions?

Let’s take a look at another of Frege’s arguments ...

‘Now that part of the thought [i.e. proposition] which corresponds to the name 'Charly' cannot be Charly herself;

[...] For each individual piece [...] which is part of Charly would then also be part of the thought that Charly is a secret agent.

But it seems to me absurd that pieces of Charly, even pieces of which I had no knowledge, should be parts of my thought [i.e. proposition].’

Frege, 1980 p. 79

I was just asking,

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

What distinguishes the contents of mental states?

- sentences?

- utterances?

- propositions

-- but not Lewisian propositions

-- maybe Russellian propositions?

-- maybe Fregean propositions?

One good argument for this thesis (Charly/Samantha);

one bad argument (Charly cannot be a part of a proposition).

/ex/TorF/qq/Russellian propositions are not adequate for distinguishing the contents of mental states for the same reasons that Lewisan propositions are not adequate|Russellian propositions enable us to distinguish the thought that Charly is a secret agent from the thought that Charly is a secret agent and 2^16 is 65536.|Russellian propositions enable us to distinguish the thought that Charly is a secret agent from the thought that Samantha is a secret agent|Russellian propositions enable us to distinguish the thought that Charly is Charly from the thought that Charly is Samantha

Why Senses Aren’t Descriptions

\section{Why Senses Aren’t Descriptions}

\emph{Reading:} §Kripke, S. A. (1980). Naming and necessity. Library of philosophy and logic. Blackwell: Oxford, rev. and enlarged edition., §§2.1 of Michaelson, Eliot, and Marga Reimer. ‘Reference’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2019. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/reference/.

Recall ...

What are senses?

whatever attribute of propositions (or their components) explains the difference in informativeness between propositions concerning the same object and property.

ways of thinking about objects.

descriptions of objects ??

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Charly is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Charlie>

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Samantha is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Samantha>

If senses are descriptions, the Fregean proposition which we might express by saying ‘Charly is a secret agent’ is (roughly):

<S, the missing secret agent>

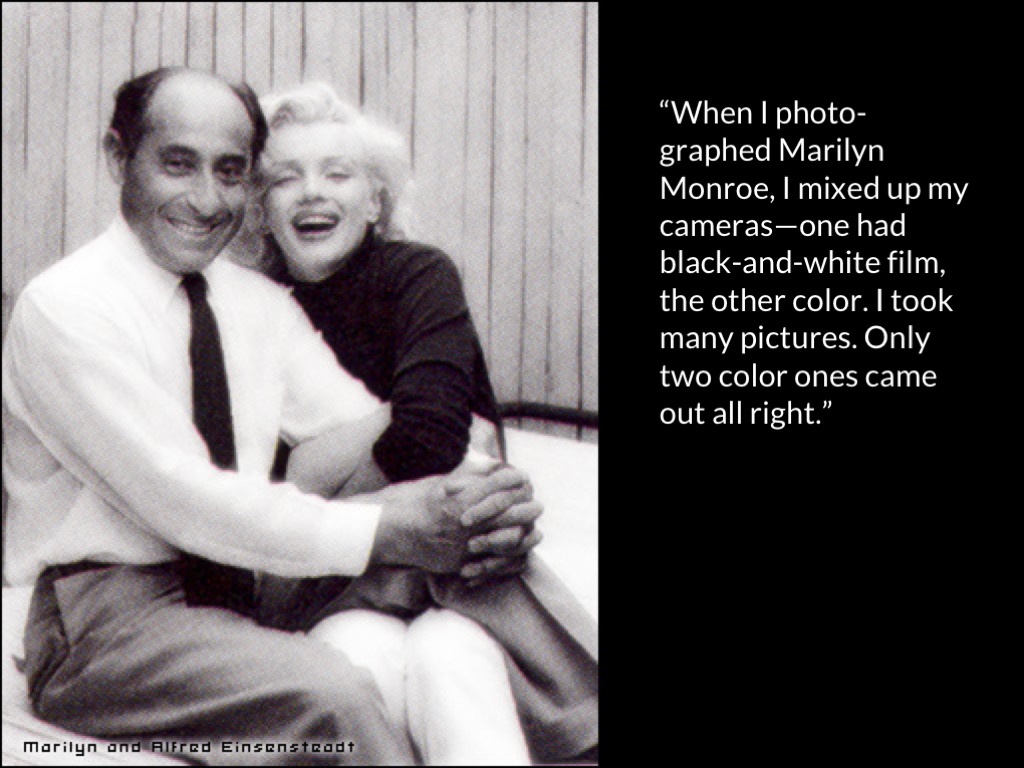

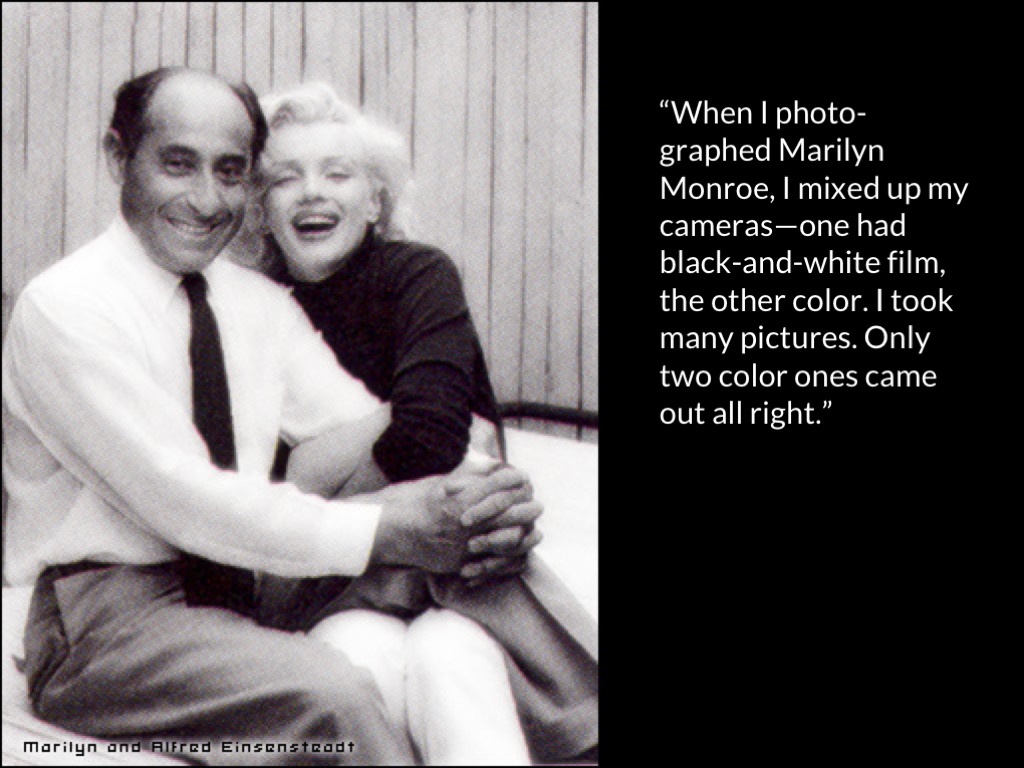

Let me introduce you to Alfred Eisenstaedt,

the photojournalist who mixed up his cameras while photographing Marilyn Monroe.

He’ll be interesting to us in a moment.

Alfred Eisenstaedt lived in Jackson Heights.

The photojournalist who mixed up his cameras while photographing Marilyn Monroe lived in Jackson Heights.

Counterfactual possibility: Eisenstaedt couldn’t make it so Martha Holmes (who lived in Manhattan) photographed Monroe.

The two propositions are not equivalent because there is a possible world in which one is false and the other true (Kripke, 1980).

Assume senses are descriptions.

Then equivalent Fregean proposition would be used to distinguish the contents

of these mental states:

your thought that

Alfred Eisenstaedt lived in Jackson Heights;

and your thought that

The photojournalist who mixed up his cameras while photographing Marilyn Monroe lived in Jackson Heights.

But these are not the same thought.

So senses are not descriptions.

Kripke, 1980

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Charly is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Charlie>

The Russellian proposition which we might express by saying ‘Samantha is a secret agent’ is:

<S, Samantha>

If senses are descriptions, the Fregean proposition which we might express by saying ‘Charly is a secret agent’ is (roughly):

<S, the missing secret agent>

Recall ...

What are senses?

whatever attribute of propositions (or their components) explains the difference in informativeness between propositions concerning the same object and property.

ways of thinking about objects.

descriptions of objects ??

/ex/TorF/from/Assume senses are descriptions|Then equivalent Fregean proposition would be used to distinguish the contents of these mental states: your thought that Alfred Eisenstaedt lived in Jackson Heights; and your thought that The photojournalist who mixed up his cameras while photographing Marilyn Monroe lived in Jackson Heights|But these are not the same thought./to/[mising]/qq/The conclusion of this argument could be that senses are not descriptions|The conclusion of this argument could be that Frege is wrong to distingish sense and reference|The conclusion of this argument could be that Fregean propositions do not allow us to individuate mental states

/ex/q/Using your own example, reconstructe Kripke’s argument that for the conclusion senses are not (all) descriptions

Conclusion on Senses and Reference (So Far)

\section{Conclusion on Senses and Reference (So Far)}

\emph{Reading:} §Kripke, S. A. (1980). Naming and necessity. Library of philosophy and logic. Blackwell: Oxford, rev. and enlarged edition., §Campbell, J. (2011). Visual Attention and the Epistemic Role of Consciousness. In Mole, C., Smithies, D., and Wu, W., editors, Attention: Philosophical and Psychological Essays, page 323. Oxford University Press.

conclusion

In conclusion, ...

The argument for the postulating sense can be framed using the notion of a proposition.

‘[A]ll that anyone has been able to think of is that different [senses] are [...] descriptions’ (Campbell, 2011 p. 340)

Senses are not descriptions (Kripke, 1980).