Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

(If the slides don’t work, you can still use any direct links to recordings.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Lecture 12:

Mind & Reality

\def \ititle {Lecture 12}

\def \isubtitle {Mind & Reality}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\textbf{\ititle}: \isubtitle

}

\iemail %

\end{center}

Q

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

\citep{Davidson:1971fz}.

‘The problem of action is to explicate the contrast between

what an agent does

and

what merely happens to him‘

\citep[p.~157]{frankfurt1978problem}.

Frankfurt, 1978 p. 157

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

remind yourselves of the Argument from Spiders

Are We Sure Spiders Don’t Have Intentions?

\section{Are We Sure Spiders Don’t Have Intentions?}

\emph{Reading:} §Jackson, Robert R., and Fiona R. Cross. ‘Spider Cognition’. In Advances in Insect Physiology, edited by Jérôme Casas, 41:115–74. Spider Physiology and Behaviour. Academic Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-415919-8.00003-3., §Buehler, D. (2019). Flexible occurrent control. Philosophical Studies, 176(8):2119–2137.

Sam’s Objection to Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Good example of not trusting a philosopher

you were like well maybe they do have intentions right and i thought to

myself yeah and then i thought to myself after that conversation i

thought to myself steve you better go and like really check that you're

up to date on spiders you better check that you're really up to date on

spiders because if sam's objection works that's going to be embarrassing

right being refuted by a first year you know you're supposed to be like a

professor of philosophy and still the first year can take you down right

and it happens more than once happens more than once um on the other hand

that's what i like right that's why i'm here that's the good thing about

it

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control.

[...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

\citep{buehler:2019_flexible}

Buehler, 2019

Why is this relveant?

1. There is a contrast between actions and mere happenings in the lives of spiders.

2. The contrast in the lives of humans is the same.

3. Spiders do not have intentions, nor do they deliberate about what to do.

Therefore (from 1 & 3):

4. The contrast in the case of spiders cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Therefore (from 2 & 4):

5. The contrast in the case of humans cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Jackson & Cross, 2011 figure 3

caption:

‘Portia labiata (left) from the Philippines stalking a spitting spider, Scytodes pallida (right).

Approaching head on would bring Portia into Scytodes’ line of fire. Instead,

Portia executes a planned detour by which it approaches this dangerous prey from the rear.’

‘Distances between Portia and the surrounding array are too far for

Portia to cross simply by leaping. The only way Portia can reach its

prey is to walk down to the floor and over to one of the two poles,

climb it and then follow the path to the prey. However, once on the

floor, Portia can no longer see the prey.’

‘P. labiata foregoes the detour and instead takes the shorter, faster head-on approach when the spider it sees in a web is a Scytodes female that is carrying eggs (Li and Jackson, 2003). This makes sense because Scytodes females carry their eggs around in their mouths. Egg-carrying females can still spit, but only by first releasing their eggs (Li et al., 1999). Being reluctant to release their eggs, egg-carrying females are, for P. labiata, less dangerous as prey.’

But is this prey-specific activity really evidence of planning? No!

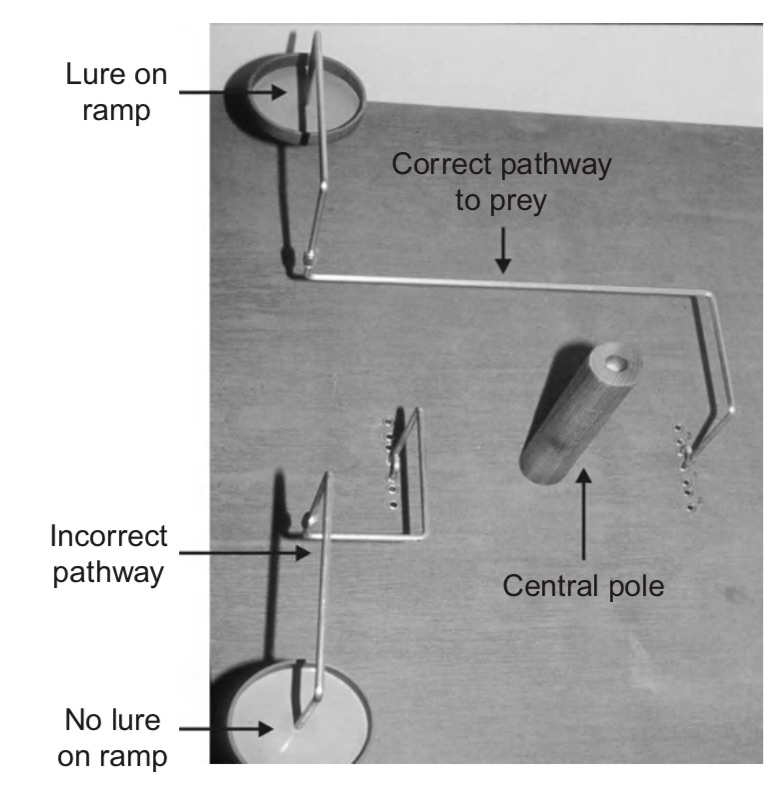

Jackson & Cross, 2011 figure 2

caption:

‘Apparatus used for testing Portia fimbriata’s detour-planning

ability. Portia was on top of the central pole before each test

began. The prey item (lure made by mounting a dead spider in

life-like posture on a cork disc) (not shown) was on one of the two

ramps (whether on the left or the right ramp decided at random).

Portia viewed the prey while on top of the central pole but could not

see the prey when it went down the pole. By consistently taking the

route that leads to the prey, Portia demonstrates ability to plan

ahead.’

‘P. labiata foregoes the detour and instead takes the shorter, faster head-on approach when the spider it sees in a web is a Scytodes female that is carrying eggs (Li and Jackson, 2003). This makes sense because Scytodes females carry their eggs around in their mouths. Egg-carrying females can still spit, but only by first releasing their eggs (Li et al., 1999). Being reluctant to release their eggs, egg-carrying females are, for P. labiata, less dangerous as prey.’

‘Portia’s task always came down to choosing which one of two paths

would lead to the prey. Sometimes Portia had to walk past the wrong

pole before reaching the correct pole, and sometimes Portia had to

head directly away from the prey before accessing the correct pole.

Yet, regardless of the details and despite having no prior experi-

ence of taking or even seeing the paths available in the experiments,

Portia chose the correct pole significantly more often than the wrong

pole.’

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control. [...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

\citep{buehler:2019_flexible}

Buehler, 2019

never trust a philosopher

opinions

There is the internet for that.

Although i'm not kind of really up with

facebooking my ticktock snapchats on twitter

and all that kind of thing (did I say it right?),

i do have the

internet so if i want an opinion i know where to go.

1. There is a contrast between actions and mere happenings in the lives of spiders.

2. The contrast in the lives of humans is the same.

3. Spiders do not have intentions, nor do they deliberate about what to do.

Therefore (from 1 & 3):

4. The contrast in the case of spiders cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Therefore (from 2 & 4):

5. The contrast in the case of humans cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Why is this just orange? Because showing that spiders can plan future actions

is arguably not enough to show that they have intentions.

It’s just that, having shown this much, it seems foolish to assume we know that they

lack intentions.

it's very important not to go too quickly so there's a temptation here

to say gosh you know the objection is right or the objection is wrong

but in doing philosophy we're thinking in slow motion so we want to go

very slowly here what are the options that we have

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

Which would you choose at this point?

‘... concepts which are inapplicable to spiders and their ilk.’

Frankfurt 1978, p. 162

‘Many animals that do not have conceptual intentions flexibly exercise agential control. [...] Spiders very likely do not have them’

\citep{buehler:2019_flexible}

Buehler, 2019

Difficulty is going to be to able to combine the view that

spiders exercise agential control while holding that they

lack intentions.

Later we might see that Bach’s notion of ‘executive representation’

allows us to do this.

For what it’s worth (nothing), I have argued that just this

combination is possible. But doing that would take us too

far away from the more basic issues.

(Generality vs depth.)

1. There is a contrast between actions and mere happenings in the lives of spiders.

2. The contrast in the lives of humans is the same.

3. Spiders do not have intentions, nor do they deliberate about what to do.

Therefore (from 1 & 3):

4. The contrast in the case of spiders cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Therefore (from 2 & 4):

5. The contrast in the case of humans cannot be explicated by appeal to intention.

Can you maintain both of these?

Dilemma:

Horn 1: accept that spiders to have intentions

Horn 2: deny that spiders have intentions: the guidance of their actions depends on some other

kind of representations of actions.

But this appears to undermine any grounds to accept premise 2.

In one case the contrast depends on whatever kind of intentions humans have,

whereas in the nonhuman case, the contrast depends on different kinds of state.

So there are distinct contrasts that resemble each other, not one contrast.

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

might be helpful to think about human infants ...

This is what we will do next, using an argument due to Bach.

But first let me wrap up what we’ve achieved

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention.

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders [??]

\section{Bach’s Objection}

\emph{Reading:} §Bach, Kent. ‘A Representational Theory of Action’. Philosophical Studies 34, no. 4 (1978): 361–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00364703., §Bratman, M. E. (1984). Two faces of intention. The Philosophical Review, 93(3):375–405.

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention.

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders [??]

Options:

try a different line

switch animals

further explicate the notion of intention

intentions as elements in plans

vs

representations which somehow guide actions

Bach offers a further argument

‘some actions are performed too automatically, routinely, and/or unthinkingly to be in any way

intentional.

There need be nothing intentional about scratching an itch [...]

There need be nothing intentional

about [...] ducking under a flying object.

fight scence from Chaplin’s the Kid around 27:15

Impulsive actions are not

intentional’

\citep[p.~363]{bach:1978_representational}.

Bach, 1978 p. 363

Use this to construct an objection to Davidson’s View

(along the lines of Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders).

But is the objection any good?

1. Ducking under a flying object is an action.

2. When you duck under a flying object, there is no need not be an intention you are acting on.

I was passing a farm the other day and there was a sign outside saying

‘Duck, eggs’. I spent some time trying to work out why they had used a comma

in that sign, then it hit me.

Therefore:

3. Intention is not the mark that distinguishes actions.

Why accept this premise? Is there any coherent view on which it’s not an action?

Is that what Bach actually says? No!

After being bitten by spiders, we should be more cautious here.

Seems a bit mad to suppose this to me, but it’s not a matter of opion.

We need arguments either way.

‘it is unclear whether we can appeal to a general intention to protect myself from flying

objects to explain [...] why my catching the ball [or ducking Bach’s flying object] is intentional’

Bratman, 1984 p. 395 footnote 26

\citep[p.~395 footnote 26]{Bratman:1984jr}.

\section{Conclusion on Action}

conclusion

In conclusion, ...

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention.

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions [??]

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

Consider that the spider’s movements walking on the web are guided by the web’s structure.

And similarly for your actions when driving on the roads.

(Guiding is not only something you do, but something that is done to you.)

Explanatory vs Justificatory Reasons

\section{Explanatory vs Justificatory Reasons}

\emph{Reading:} §Dretske, F. (2006). Perception without awareness. In Gendler, T. S. and Hawthorne, J. O., editors, Perceptual Experience, pages 147–180. OUP, Oxford., §Alvarez, Maria. ‘Reasons for Action: Justification, Motivation, Explanation’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2017. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2017. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/reasons-just-vs-expl/.

this weekend i was walking to a party on saturday night on a muddy path in

the dark and i fell over a log i tripped over a log and i landed on my face

in the mud covered with mud in my party gear so that was a memorable event

but it wasn't an action tripping over the log was was not an action uh

whereas of course walking to the party was so what is it that distinguishes

actions it's not the actions are somehow the most memorable events in our

life what is it that distinguishes actions from other events in our lives

i arrived at the party you know rather covered in mud right which is not

the traditional way to arrive at a party

Steamboat Bill, around 59:30

‘we have to carefully distinguish explanatory reasons, the reasons why S does A or believes P,

from justifying reasons, S’s reasons for doing A or believing P, the reasons S (if able)

might give to justify doing A or believing P.’

\citep[p.~168]{Dretske:2006fv}.

Explanatory reason example: Steve arrived looking like that for the reason that the path was so muddy.

Justifying reason example: Steve walked to the party because he believed it would be more romantic.

Explanatory Reasons

Mark: factive (must be true); no point of view.

Why did Steve arrive looking like that?

- Because the path was so muddy.

Why did the sign fall over?

- Because the path was so muddy.

the explanation that you're giving here is much like the explanation

you might get for any other naturally occurring event one that didn't

involve an agent right so uh as i was walking along the muddy path

you know it was sort of waterlogged and dark and i noticed that there

wasn't just a tree that had fallen over but also one of the signs

pointing me in the direction of the well i guess it was the village

uh whatever it was it was dark i couldn't tell anyway the thing had

fallen over right why had it fallen over because the the ground was

so muddy right there was no firm ground to support the foundation for

that sign so in this case you've got an agent in that case you

haven't got an agent

Justificatory Reasons

Mark: nonfactive (can be false); agent’s point of view.

Why did Steve walk to the party?

why did i why did i walk to the party right now there i was with mrs b

and we were staying at a hotel at one end of basing stoke and the party

was somewhere else in beijing stoke not been to basingstoke before um

interesting place and i thought to myself you know what it would be

really romantic to take mrs b on a night walk under the moonlight to

the party

- Because he believed it would be more romantic.

what i didn't realize is that the path

essentially went via some derelict warehouses some power infrastructure

and a railway line and was covered with mud and completely unlit right

so this was not this was not romantic this was not romantic as it

happened

It wasn’t; it was too muddy.

what you're

appealing to here and giving the justifying explanation is not the fact

that it was romantic but the belief that i had that it was romantic or

that it would be romantic a belief that turned out to be false

uh now you might say look well steve uh maybe it was romantic in some

way but not not in any relevant way so if i was taking not mrs b but

princess fiona then you know perhaps it would have qualified as

romantic

and although mrs b clearly like fiona descends from ogres

she's not really into you know muddy walks big pools of water tree

trunks anyway that kind of thing right she wasn't impressed whatsoever

This is not to say that justificatory reasons have to be false, just that they may be.

so the important thing here is that when we're giving the justifying

reasons the considerations that we're giving are not necessarily facts

the reason that justifies my choice of approach to the party walking as

opposed to taking our bikes or getting a taxi is something it's a

consideration which is not a fact it's a consideration that it would be

romantic it wasn't romantic has the consideration linked to the action

by my belief in this case so one of the things about explanatory versus

justifying reasons is that the explanatory reasons have to be factive

whereas the justifying reasons are non-factive so if you go back to

that sign and i say why did the sign fall over because it was muddy if

it turns out that it wasn't muddy then i haven't given you an

explanation at all when we come to the justifying reasons it's

completely irrelevant whether walking to a party in beijing stoke along

a dark unlit muddy path is romantic or not right that can still be the

justifying reason

second thing about justifying reasons is that they're going to capture

the agent's point of view right the choice that i made is explained

from my point of view by consideration which i took to be an

explanatory reason but we just turned out wasn't an explanatory reason

whereas when you're giving when you're citing genuinely explanatory

reasons what you're providing is something which makes sense from no

point of view whatsoever

Justificatory Reasons and Intentions

\section{Justificatory Reasons and Intentions}

How is this relevant to our question?

Q

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

A.2

Actions are events for which there are justifying reasons.

Do you understand the answers?

Are they one answer or two?

Among all the considerations which are, or might be, explanatory reasons for an action, what determines which are (the agent’s) justifying reasons?

Ayesha

Desire: I catch the bus.

Belief: Running is a way of arriving at the stop before the bus leaves.

Intention: I run to the bus stop.

Beatrice

Desire: I catch the bus.

Belief: Running is a way of geting the driver to wait by signalling my desire.

Intention: I run to the bus stop.

They have different justifying reasons. In virtue of what is this true?

In part it’s a matter of what they believe.

But not just this. After all, they might have the same beliefs and yet not

count the same things as reasons which justify their running.

(Ask each, Why did you run?)

so can we answer this question among all of the potential including

some of the actual considerations which would explain an action which

of those are among the agents justifying reasons by appealing to belief?

no we can't do that we definitely can't do that we can't do that steve

for the very simple reason that aisha and beatrice may have lots of

other beliefs as well

in particular aisha may well believe that

running is a way of getting the driver to wait by signaling her desire

but it still might not be among the justifying reasons that she has

it's also not going to be enough just to appeal to desire because in

both cases these are people who desire to get on the bus that's their

their firm desire they want to get on the bus right they're going to a

party in being they've got to get there before it gets too dark tonight

so they need we need to think about more than just the desires and the

beliefs we need to think about their intentions ...

what's important about the justificatory reason for aisha is not

merely the fact that she believes it but that this belief plays that

appropriate role in getting her to form the intention that she runs for

the bus it's not the mere fact of belief it's the role of belief in

shaping her intention that makes it the case that the thing she

believes perhaps wrongly that running is a way of arriving at the stop

before the bus is a justificatory reason for her action

likewise for

beatrice what makes it the case that running is a way of getting the

driver to wait by signaling her desire is a justificatory reason is the

fact that this belief plays an appropriate role in her forming the

intention

very clear very simple idea steve very simple idea you're

making it difficult by spelling it out so slowly oh philosophy thinking

in slow motion

Among all the considerations which are, or might be, explanatory reasons for an action, what determines which are (the agent’s) justifying reasons?

among all the considerations which are or might be explanatory reasons for

an action what determines which are the agents justifying reasons?

It’s those of her beliefs which lead to her forming the intention which guides her action.

My suggestion is that it‘s not just facts about her beliefs that‘s

part of the story ...

but it‘s facts about those of her beliefs which lead

to forming the intention.

but then you‘re like steve, Which intention?

when i say *the* intention that‘s very confusing

the intention which guides our action

Accepting the second answer (A.2) seems to commit us to accepting the first answer (A.1).

Of course there are probably ways to avoid this commitment.

(I didn’t offer an argument.)

So, more cautiously, let’s say that accepting A.2 would motivate accepting A.1

I haven’t said anything about the converse route.

Q

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

A.2

Actions are events for which there are justifying reasons.

\section{Conclusion on Action (extended version)}

conclusion

In conclusion, ...

What is the mark that distinguishes actions?

Davidson’s View

It is intention (or justifying reasons).

Objection:

Frankfurt’s Argument from Spiders

Bach’s objections from absent-minded, instinctive and impulive actions [??]

Frankfurt’s View

Action is ‘behaviour whose course is under the guidance of an agent’.

Two Problems:

What is guidance?

When is guidance ‘attributable to an agent’?

Consider that the spider’s movements walking on the web are guided by the web’s structure.

And similarly for your actions when driving on the roads.

(Guiding is not only something you do, but something that is done to you.)

Contrast Frankfurt, 1978 with Bach, 1978

‘though attempting to account for how action is initiated,

they fail to deal with how it is executed.

Nevertheless, I believe Causalism to be fundamentally correct’

\citep[p.~361]{bach:1978_representational}

Bach, 1978 p. 361